Why do we organize expeditions to abandoned Gulag camps? What do these trips bring? What specific conclusions can they help us reach? We attempt to answer those questions in the following article, which is an abbreviated, popularising version of an academic text in the book of Archaeology of Dictatorship published in 2020 by the Oxford-based British Archaeological Reports. If you are interested in reading the original piece, we would be glad to send it to you in PDF form; you could also order the whole book.

Lukáš Holata, archaeologist with Gulag.cz, University of South Bohemia, České Budějovice

Štěpán Černoušek, chairman and founder of Gulag.cz

*Example of the 360° panoramic photography technology (virtual tour of the interior of the prison barracks in the Barabanikha camp by Pavel Blažek): *

Introduction

It may seem to some that archaeologists have devoted their lives to seeking out valuable goods. However, the reality is utterly different – they are very far removed from the work of ‘treasure hunters’. Their primary interest is (or ought to be) to know better and understand the past human world; they examine not only ‘ancient civilizations’ but also the period of the 20th and 21st century. To do this, they use the so-called ‘archaeological record’, meaning non-written evidence of the period in question. This evidence chiefly concerns artefacts which are, simply put, human creations of any kind – from the most ordinary items to the extraordinarily sophisticated ones. But it also includes human settlements, fields, production areas, or the appearance of the contemporary landscape. Therefore, it does not mean that artefacts are exclusively found underground; a considerable volume of the human activities’ remains are still on the surface and can thus be (relatively) easily documented, even without ‘digging’.

This is just the case with the correctional labour camps spread around the extensive territory of the former Soviet Union that were part of the giant Gulag system – a penal element of the Communist regime’s repressive apparatus. The camp remnants represent unique archaeological sites; they are practically entrance-free museums, time capsules that still preserve an exceptional testimony to one of the most tragic chapters in human history.

Photogrammetric 3D model of prisoner's work boot found in one of the abandoned camps (author: Jindřich Plzák):

A significant amount of literature about the Gulag is readily accessible – numerous memoirs by prisoners who survived, lists of persecuted individuals, or academic studies examining assorted instruments of Soviet totalitarian power. However, we do not find any publications on systematic archaeological research, in contrast to, for instance, concentration and POW camps in Europe, which have been of interest to archaeologists for 30 years. The extreme remoteness of the places where well-preserved Gulag camp remains lie is an important factor. However, this does not represent the biggest problem: the independent study of repression is deliberately restricted by the current Russian regime, unfortunately still increasingly, and the situation in Russian society. Since Vladimir Putin’s accession to power in 2000, the Russian state has striven to support a positive perception of the Soviet past, in which it finds reinforcement for its authoritarian style of government; in many regards, the USSR era should represent a positive chapter in the history of which current Russia is a successful heir. It does not mean that today’s Russian state has denied the millions of victims or the very existence of the Gulag. Instead, it interprets them as a kind of error without an obvious culprit that has nothing to do with today. This fact leads to the crushing of independent research into the entire Gulag system, the sidelining of discussion about responsibility and the extent of Soviet repression, and insufficient care of still-preserved camp remains – places through which, according to various estimates, between 12 and 20 million people passed, with roughly one in ten not surviving.

The unfortunate consequence of this is that we are losing this unique testimony to the crimes of communism due to natural processes and human intervention. It is, however, in our interest to maintain those places in the memory, if nothing else out of respect for the innocent victims of the Gulag and other forms of Soviet repression; these included not just citizens of the USSR but thousands of Czechs or citizens of Czechoslovakia and many different nationalities from Europe or America.

Three expeditions by the Gulag.cz team to what is known as the Dead Road (a railroad construction of Gulag camps no. 501 and 503 between Salekhard and Igarka) in Siberia’s polar regions (in 2009, 2011 and 2013) and one to the remains of uranium mining at the Borlag camp in the Kodar Mountains in the Zabaykalsky Krai (2016) are thus pretty rare in this respect. They followed on documentations carried out by Russian enthusiasts (mainly from the Memorial association), predominantly in the 1980s and 1990s (Moscow’s Museum of the Gulag began organizing expert expeditions a few years ago; many spots are also visited by tourist groups with no specialized background, frequently leading to the remnants dismantling). Our expeditions’ main objective was to document the still preserved camp remains in as much detail as possible in the given conditions and to share the results with the general public – see the Gulag Online Museum project, the documentary Journey to the Gulag as well as the creation of an educational tool in virtual reality. Nevertheless, such activity made it possible to significantly expand the contemporary knowledge of the repressive apparatus in the Communist totalitarian system; until now, we could only imagine such places or infer them from witnesses’ recollections, as the exact form of remaining constructions, buildings, or equipment was little known. The specific findings that these expeditions delivered will be outlined briefly in the following lines.

Gulag camps as unique archaeological sites

Qualified estimates put an astronomical number of 30,000 Gulag camps spread over a vast territory covering diverse climatic zones as well as contrasting types of natural and cultural landscapes; they were located both in completely remote regions and directly in urban locations or their immediate vicinity. Indeed, many current towns grew out of former labour camps. For this reason, it is impossible to provide a comprehensive summary that applies to all cases. Not surprisingly, the best-preserved Gulag remains are to be found in the most remote, hardest to access, and essentially uninhabited parts of Siberia.

For such cases in particular, our existing knowledge may be summed up in the following theses:

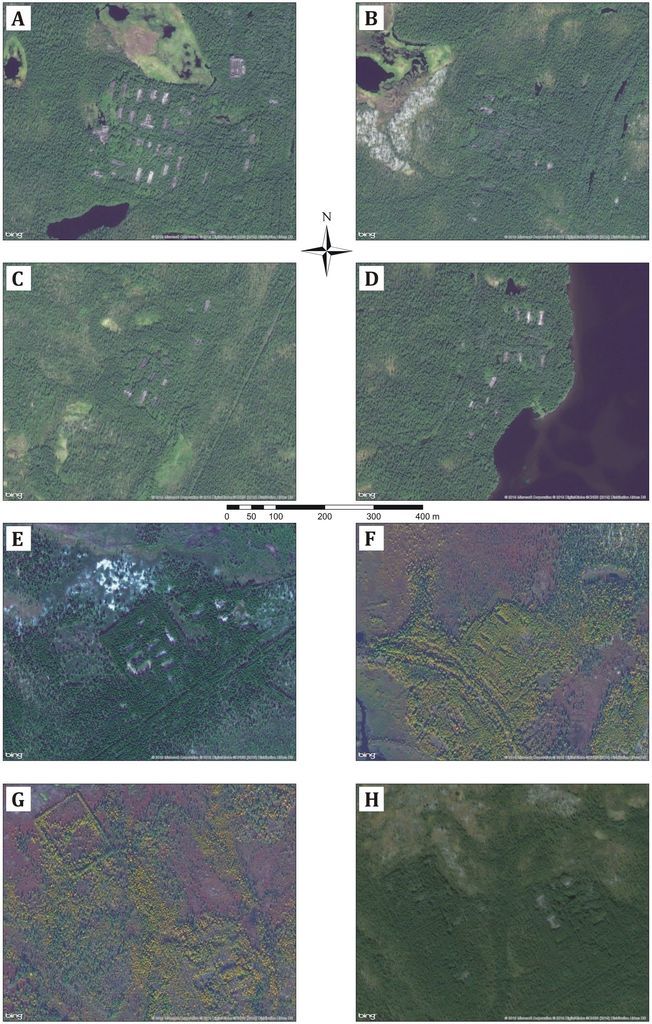

a) The exact camps’ locations are generally unknown; they have to be searched for at length on old military maps and satellite images in particular – alongside the current ones, we also draw on accessible spy satellite photos taken by the American CIA (especially the Corona project of 1960–1972).

b) No further information is available on a considerable number of the camps that have been discovered. In many cases, we do not even know their names (access to Russian archives is restricted; often, there are only random references to go on).

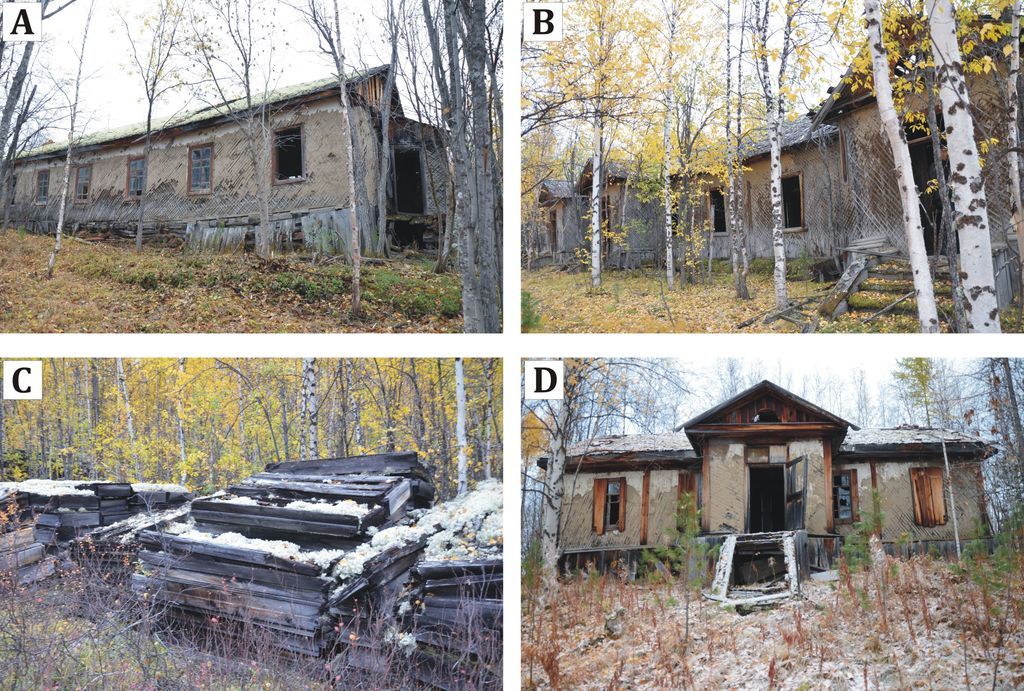

c) Even in the most remote regions, the degree to which camp remains are preserved differs radically. Many were systematically liquidated when they were being abandoned. Some camps have been dismantled by hunters and other people for building material and firewood. Further camps have succumbed to the elements and the simple passage of time.

d) The degree of camps’ preservation is also determined by their original purpose; for instance, temporary ones in which prisoners lived in tents (!) are today practically undetectable archaeologically (in some cases, spatial delineation can only be made out on satellite images, thanks to a sharp boundary between different types of vegetation).

e) There are marked differences in the number of artefacts to be found in individual camps. It is undoubtedly shaped by various circumstances, though we regard the manner they were abandoned as the key factor. Many camps display signs of careful evacuation; thus, most equipment was taken away, causing us to miss a considerable amount of information.

f) Despite the multiple ways original situations were disturbed, some camps’ quality of preservation is so extraordinary as to merit the description ‘intact’, meaning virtually untouched (something archaeologists working on other subjects almost never encounter). These were abandoned hastily, even chaotically (as seen in the discovery of a letter in a stove that someone did not have time to burn), and were left to their fates while still being protected from significant destruction. To this day, they consist of still-standing structures, while there are original fittings inside buildings, and the entire ‘zone’ with the surroundings is literally filled with artefacts.

g) A significant number of artefacts in the ‘intact camps’ remain in the places where they were used or left by the people of that time. This revives various aspects of camp life, both obvious or predictable (e.g., the number of persons in a prison barracks deduced from the arrangement of bunk beds) and those that have been little known so far – for instance, a barrel bearing the inscription ‘Drinking Water’ still stands in the hallway of a prison barracks, brooms and mops lean against the wall or chimney in the middle of a sleeping area, the remnants of newspapers beneath windows evince their secondary use as insulation, fragments of letters along the wall suggest where they were kept… These situations make these locations extraordinarily evocative as if the past has almost come to life. Dark solitary cells, fitted with only a narrow bench and wooden bucket for excrement, are genuinely chilling. The dog bowls that still lie at the kennels infuse these places with a post-apocalyptic atmosphere. And we could offer plenty of more examples.

The course of archaeological research

The harsh environment of Siberia and remoteness from civilization determine how the archaeological survey is carried out. Of course, it must be conducted differently than in ‘regular’ sites. Well-preserved camp complexes can generally only be reached on foot – through rugged, hostile terrain with wetlands, flooded rivers, and millions of mosquitoes. On top of that, all tools and energy sources must be borne on one’s back – we can only bring what we can carry, meaning light equipment only.

Therefore, on the one hand, research methodology focuses on state-of-the-art rapid data collecting procedures using a camera – photogrammetry for creating 3D models of artefacts (involving any objects, buildings, the entire camp, and other associated areas) and 360° panoramic photography to produce virtual tours. On the other hand, it involves a return to the methods of 19th century archaeological documentation applying pencils, paper, and the Pythagorean theorem. In any case, it is always non-invasive archaeological research, which leaves the discovered situation completely undamaged and undisturbed. However, due to the difficult travel, it is highly restricted in terms of time; thus, it is possible to document a mere fraction of the facts that would be necessary. Setting a list of priorities in advance is a must. The whole expedition then requires daily improvisation and physical robustness, mental resilience, and ability to survive in nature on the part of researchers.

Example of 360° panoramic photography (virtual tour of solitary confinement in the Barabanikha camp, author Pavel Blažek) and photogrammetric 3D model of a stretcher (uranium mine in the Marble Gorge, author Radek Světlík):

So what has the archaeological research of the Gulag brought us? The data obtained so far may be summarised in four basic topics.

1) The impact of the Gulag on the natural environment and the landscape appearance

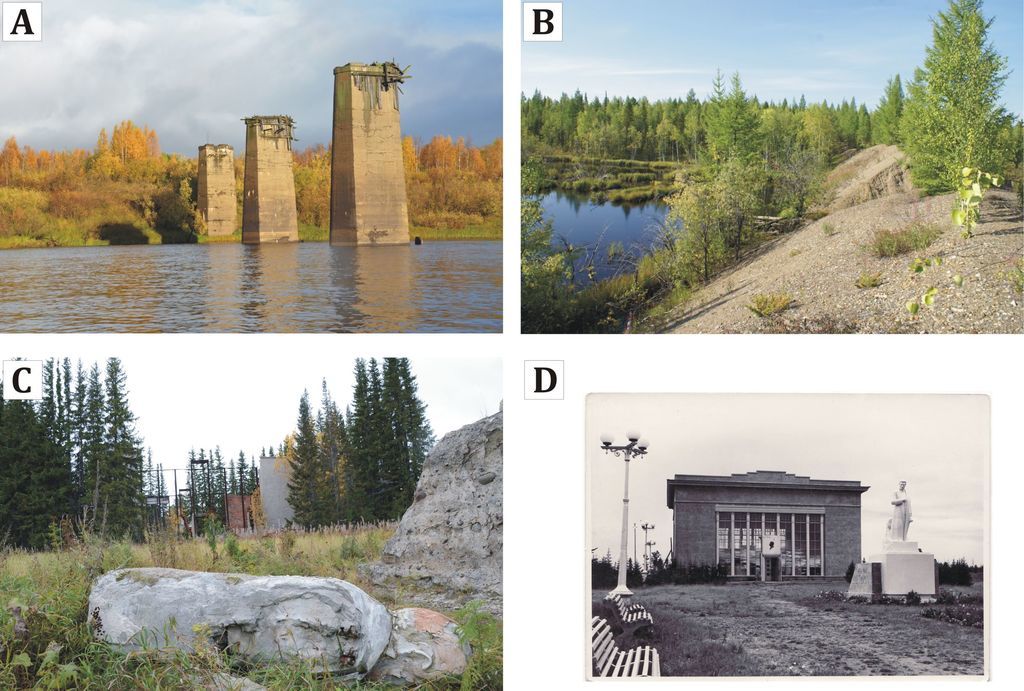

Camps are not the only type of material remains of the Gulag. Hundreds of thousands of human lives were snuffed out by daily slave labour whose results are still visible in the landscape. Examples include extensive mining areas, railroads, airports, canals…; many of these structures are still in use today. The presence of labour camps stimulated the development of not just a significant number of rural and urban settlements but of the entire cultural landscape. The whole present-day infrastructure in Kolyma, an extensive territory in the far northeast with substantial gold and precious metals mining, was created between the 1930s and 1950s just in connection with the Gulag. This naturally also brought negative consequences – an extensive area of virtually unspoiled nature will be marked by human activity forever.

The example of the Dead Road is illustrative. Although the railroad never went into operation, the created embankment with a length of several hundred kilometers and its reinforced concrete bridges remain in the polar landscape to this day. Thousands of tonnes of iron, including rusted locomotives, are scattered in places that are not even permanently occupied, slowly disintegrating in the middle of the uninhabited taiga. Contaminated soil and water sources are other issues; even though we do not have their exact confirmation, we assume that they represent a serious and unfortunately permanent disruption of the local natural environment.

2) The camps and their components reconstruction

Official records of the Gulag tend to be administrative in nature. Memoirs of survivors, logically, focus on descriptions of powerful experiences and hardships rather than precise locations and detailed camp structures' appearances. Only archaeological research can deliver this type of information. Surveys of camp complexes with varying levels of preservation have revealed several characteristic and recurring features that give us a more concrete idea of how they looked:

a) Despite general unification, the appearance of camps differed according to where they were located. Spatial arrangement responded to the relief, and local materials were used in construction (a camp located deep in the taiga looked different at first glance than one in the arid Kazakh steppe or the suburbs of Moscow).

b) Camps varied in size, also in connection with their purpose. The biggest one we documented, the Barabanicha camp, could hold 800–1,000 prisoners and contained components not found in smaller ones. It included a hospital, a large canteen, and a prisoners’ club, equipped with a stage. Others that we visited during expeditions were intended for a maximum of 500 people. Incidentally, there were also camps for up to 15,000 prisoners, such as large transit camps.

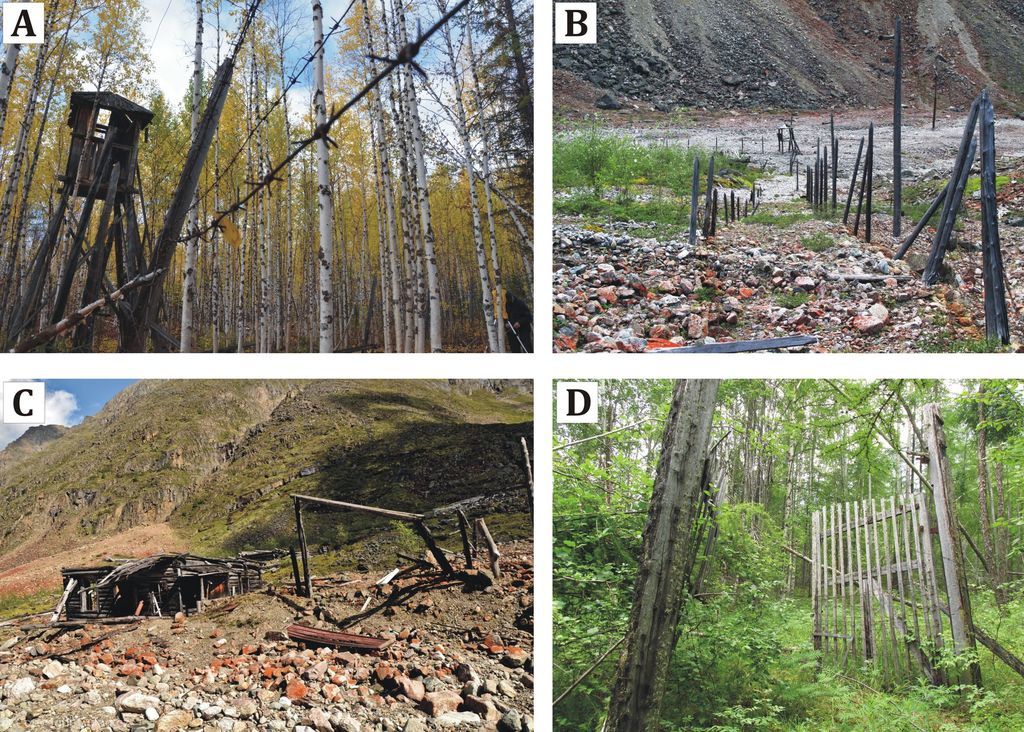

c) Each camp complex was strictly divided into two sections: (1) an administrative part, consisting of service buildings necessary for a camp operation (e.g., offices, electrical and radio stations, bakery, shop...) and accommodation for management, guards and free employees; and (2) a prison part – the ‘zone’, ‘perimeter’ – thoroughly delineated by double or even triple barbed wire fence.

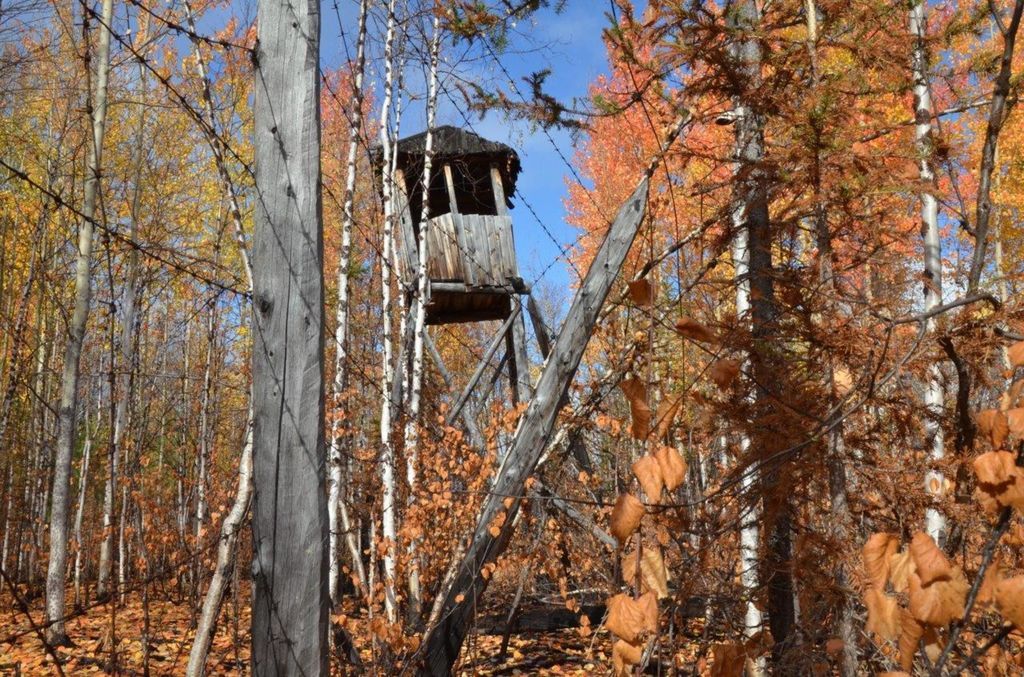

d) The zone always took on a more or less rectangular shape, with guard towers in the corners. We have also managed to document such anomaly as a camp with a single guard tower; the prevalence of administrative buildings and the absence of a correction section – the ‘prison within a prison’ – indicate its lenient regime.

e) The zone had a single entrance only – the main gate. As with Nazi concentration camps, this bore a panel with a ‘motivational slogan’ (e.g., ‘With Just Work I Will Pay My Debt to the Fatherland’).

f) Next to the gate stood a gatehouse, with its layout placed half outside and half inside the zone.

g) All buildings used by prisoners were situated in the zone: residential barracks, a social barrack containing a kitchen and canteen (usually on the opposite side from the gate), administrative buildings, bath and disinfection station, latrines (usually close to the fence), infirmary and solitary confinement cell (typically in a corner to the left or right of the gate).

h) The size of the rooms in residential buildings reflects the social status of the camp's inhabitants, signifying the level of comfort and possibility of heating in winter. The commander and management lived in smaller rooms than prisoners, who themselves did not constitute a unified category; we have also documented barracks for privileged prisoners (probably cooks and doctors), whose rooms were again smaller than standard ones.

i) The appearance of standard prisoners’ barracks could also differ, even within a single camp. Along the so-called Dead Road, we have documented two basic types of differing size, construction, and ground plan: 1) a log-construction barrack of around 26 x 8 m consisting of two mirror-inverted rooms, entered from the porch; and 2) a barrack composed of prefabricated pieces on around 40 x 8 m consisted of four rooms with separate entrances – the two central ones were for accommodation. A clay daub serving as insulation covered both types of buildings; the prefabricated parts were also filled with sawdust for the same purpose. Each type of barracks was intended for around 80–100 prisoners.

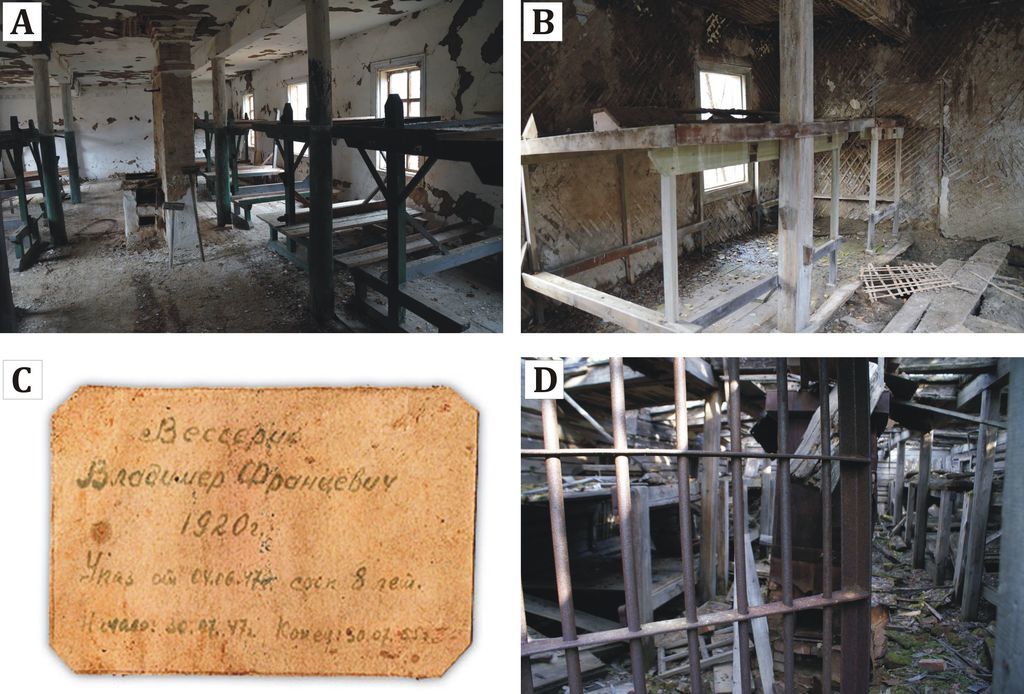

j) The interior of rooms was more or less constant: There was a small cloakroom at the entrance, bunk beds were placed along both longer walls behind the supporting columns, a small stove with a chimney stood in the middle, the floor was plank, the walls were whitewashed, and the room was fitted with electric lighting (at the Barabanicha camp we documented the remains of a coal-fired power plant; as testimonies suggest, diesel generators were operating in smaller camps).

k) Various combinations of fixed and free-standing bunk beds (known as ‘wagons’) were found in regular prison barracks. Both types identically contained four beds, each of which was marked with a card including name, relevant legal article, and sentence duration. Barracks in the Punishment camp were fitted with a continuous double strip of wooden planks along the entire room (known as ‘sploshnye nary’), without marked spots for specific prisoners.

l) Correction section differed from camp to camp, only their location in a corner to either side of the entrance is the common feature. Somewhere it looks like a small building with one room only. In other places, it was essentially a small prison with a common cell and several solitary confinement cells. In some cases, it was also enclosed by barbed wire. Also, the interior layout and form of cells varied among large correction sections. The most common was a small room of 3.5 x 1.8 m with a small window only, or even without it. We also documented such extremes as a cell of less than 1 x 1 m that only allowed standing or sitting.

3) Insights into everyday camp life

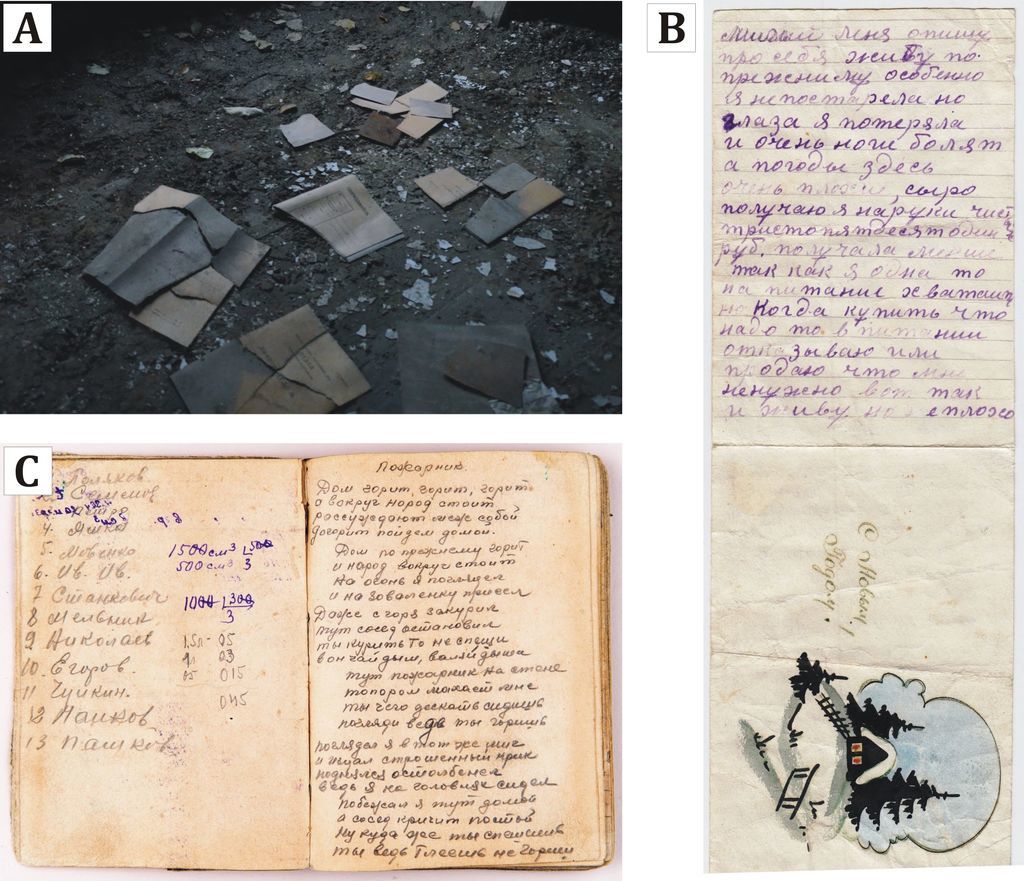

Almost all survivors’ testimonies concur that a stay in a camp was a terrifying experience. Although archaeological record does not tell us much about prisoners’ feelings, constant hunger, and exhaustion, it is a silent witness to other numerous aspects of life behind barbed wire (some have already been outlined above). One on hand, they confirm the commonly known facts – e.g., the number of cigarette butts shows how widespread smoking was while many ampoules for medicine attest to prisoners’ generally poor health or the widespread abuse of drugs by criminal prisoners, a privileged caste in the Gulag. Material evidence also brings to light such humdrum activities that are drowned out by many others in most survivors’ accounts and remain forgotten – for instance, prisoners’ barracks were apparently cleaned regularly, the numerous metal soapboxes point to a relative level of hygiene…

In contrast to the above, there is a unique testimony about life in the camp, which cannot be traced in any other way than by using material remains. Improvised items are worthy of attention. For instance, we found a ‘razor’ comprised of a blade inserted into a wooden stick or a self-made knife. These artefacts demonstrate the extraordinary ability of humans to adapt to the worst living conditions. The discovered diaries of prisoners contain poems and songs. Together with the guitar, which we also found, they indicate certain leisure time activities. These also include art, as evinced by a copy of the famous Russian painting Bogatyrs, made on coarse canvas. This motif was very popular among guards, who often had it copied by imprisoned artists. Colour, ornamental décor inside some prisoners’ barracks represents another extraordinary evidence of artistic activities among Gulag prisoners. One can only imagine whether this was also aimed at preserving the final fragments of human dignity.

4) The written word and intimate stories of unknown people

A specific task of Gulag archaeology is the acquisition of written sources that are not held in archives but scattered, in large amounts, in camp buildings. Alongside quite sporadic examples (e.g., inscriptions scratched out by prisoners), the most numerous are official documents: records of work and quota fulfilment, tables, invoices…, technical documents, drawings, and newspaper. Prisoners’ diaries and the letters they received represent, of course, exceptional discoveries; not only by providing valuable testimony on day-to-day camp reality, but some also offer literal insights into their authors’ minds. Letters, meanwhile, mediate a connection to the outside world – everyday life in the USSR (an example of such a letter you can find here). These rare artefacts together reveal snippets of life stories that would otherwise be forgotten. They preserve at least a little of past people about whom history is silent.

Conclusion

In the enormous territory of Siberia, probably the dozens more Gulag camp remains are located, in various stages of decay, also with facilities in their vicinity, which, however, have not yet been expertly documented at all. Although the current knowledge hopefully does not represent a mere drop in the ocean, it is undoubtedly still insufficient and incomplete in certain areas. Archaeological research of these sites delivers another layer of information about the communist repressive system, utterly unique evidence that cannot be obtained in any other way. Not only does it confirm and verify the testimonies of prisoners who survived or certain information in the written sources, but it also complements and enriches them. Only by using of all kinds of sources – including the archaeological, material ones – the picture of the Soviet Union’s repressive apparatus is complete.

High-quality and detailed documentation of Gulag-related objects which have not yet collapsed completely allows contemporaries to look back at places where millions of people lost their last remnants of freedom (frequently without justification), suffered from exhausting work, lack of food, failing health, and permanent harassment. Many of them met their deaths there. We can, therefore, place these tragic stories of unknown heroes into actual realities. Above that, material evidence is far harder to cast doubt on compared to the written word. Archaeologists thus provide the ‘raw data’ that presents an undeniable memento of the barbarism and perversion of the communist ideology put into practice.

P. S.

This text could never have been written without the incredible help of many other people, friends, and collaborators. The participants in the expeditions: Pavel Blažek, Martin Novák, David Těthal, and Radek Světlík took part in the mapping, documenting and evaluation of the results; other technical processing was performed by Josef Brošta (3D reconstructions of camps), Jindřich Plzák (3D models of artefacts), and Jan Vrátný (web programming).

(From the Czech original translated by Ian Willoughby; proofreading and editing by Lukáš Holata).