The unique Perm-36 Museum, created from the former GULAG camp for Soviet dissidents, has an unexpected connection to the Czech history. Located in the Ural promontory, this penal colony was part of the GULAG archipelago in the 1940s, and in the 1970s and 1980s served as a prison for Soviet dissidents, many of whom came from the Baltics and Ukraine.

Among the inmates of the facility was the globally renowned human rights defender Sergey Kovalyov, and Ukrainian poet Vasil Stus died there. There were at least 15 prisoners in the camp who served their sentences for, among other things, their protests against the invasion of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia in 1968.

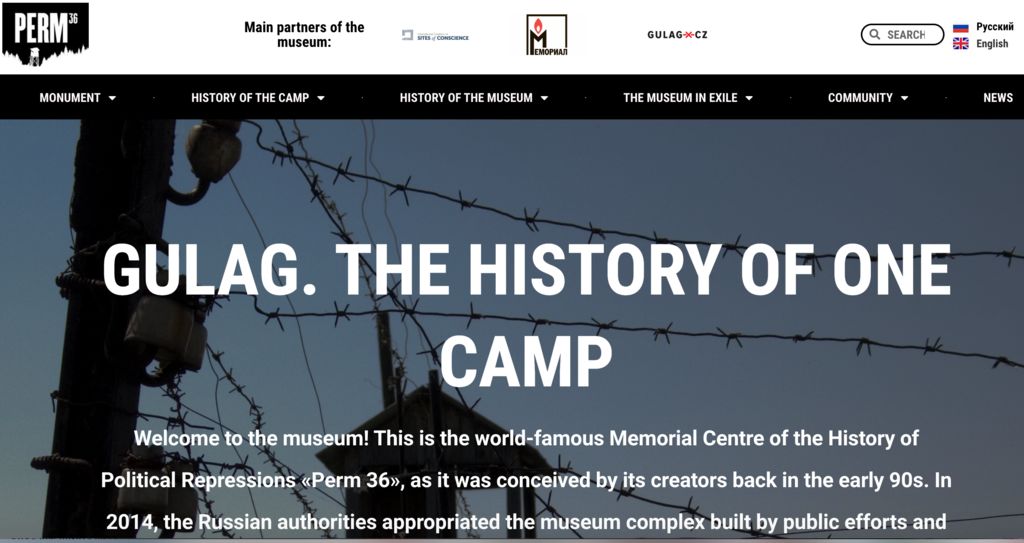

The founders of the museum transformed the abandoned labour camp into a unique memorial of Soviet repressions in the early 1990s, but in 2014 the museum fell victim to a brutal attack of the Russian government, as a result of which it was taken away from the authors and “purged” ideologically. Exhibitions commemorating Soviet dissidents were removed while exhibits celebrating the “bravery” of the guards were installed. This ideological, government-managed fraud has become a symbol of Russia’s current attitude to the dark history of Soviet repressions, rejecting independence and refusing to clearly identify the culprits behind the GULAG and repressions.

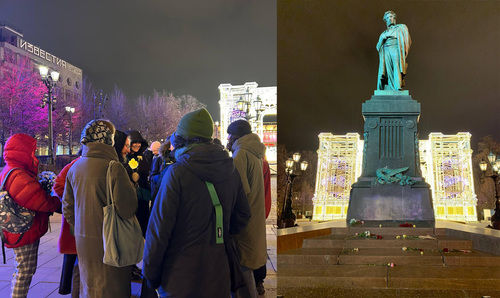

However, Viktor Shmyrov and Tatiana Kursina, who founded the museum and used to draw thousands of liberally-minded people to the area for the Pilorama festival annually, did not give up when the museum was seized from them. Despite the tightening repressions targeting the civic society and independent historians, they started working on a virtual rendition of the original museum.

They have now launched its pilot version at www.gulag-perm36.org.

On the website, you can find the museum’s former exhibits, detailed history, exhibitions, publications, and a database of all the prisoners who served their sentences in the camp.

Gulag.cz has supported the former Perm-36 colleagues for a long time. The association initiated an open letter against the takeover of the museum in 2014, and its chairman Štěpán Černoušek would update the Czech public on the developments on a regular basis (article in the Respekt magazine).

We invited the founders of the museum to the Czech Republic in the past (more information, article in Deník N). We have also been honoured to help our colleagues over the course of recent years by offering technical and administrative assistance in developing the online version of the museum, which has now been finally made public despite the increasingly difficult environment.

.jpg)